Text

-

- Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

-

- Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.[2]

History

When the Thirteenth Amendment was proposed, there had been no

new amendments adopted in more than 60 years.

Eventually the Congress and the public began to take notice, and a number of additional legislative proposals were brought forward. On January 11, 1864,

Senator John B. Henderson of

Missouri submitted a

joint resolution for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The abolition of slavery had historically been associated with Republicans, but Henderson was one of the

War Democrats. The

Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by

Lyman Trumbull (Republican,

Illinois), became involved in merging different proposals for an amendment. On February 8 of that year, another Republican, Senator

Charles Sumner (

Radical Republican,

Massachusetts), submitted a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery as well as guarantee equality.

[5] As the number of proposals and the extent of their scope began to grow, the Senate Judiciary Committee presented the Senate with an amendment proposal that combined the drafts of Ashley, Wilson and Henderson.

[6]

The Senate passed the amendment on April 8, 1864, by a vote of 38 to 6. However, just over two months later on June 15, the House failed to get the necessary two-thirds vote for passage, with 93 in favor and 65 against.

Representative Ashley was instrumental in its eventual passage. An ardent

Free Soiler before becoming a Republican, he was the House floor manager and persuaded a number of Democrats to support it.

[7] President Lincoln took an active role in working for its passage through the House by ensuring the amendment was added to the Republican Party platform for the

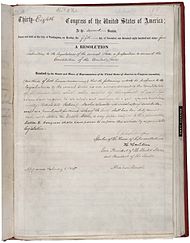

1864 presidential election and using his powers adroitly. Finally, after seven months of debate and promises of patronage, the House narrowly reached the two-thirds majority needed to pass the bill on January 31, 1865, by a vote of 119 to 56. The Thirteenth Amendment's archival copy bears an apparent Presidential signature, under the usual ones of the Speaker of the House and the

President of the Senate, after the words "Approved February 1, 1865".

[8]

Ratification

The amendment was sent to the state legislatures. The Northern states quickly ratified it. President Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth in April 1865 and

Andrew Johnson succeeded Lincoln. President Johnson strongly recommended that the ex-Confederate states ratify the amendment (and also repeal their ordinances of secession).

[9][10]

On December 18, 1865, Secretary of State

William H. Seward proclaimed the amendment to have been adopted as of December 6, 1865, when Georgia's ratification brought the total number of ratifying states to 27, of the then 36 states in the union. Florida ratified it on December 28, 1865;

[11] New Jersey in 1866; Texas in 1870;

[11] Delaware in 1901; and Kentucky in 1976.

[12] Mississippi, whose legislature voted in 1995 to do so, belatedly notified the

Office of the Federal Register in February 2013 of that legislative action, completing the legal process for the state.

[12]

Effects

Shortly after the amendment's adoption,

selective enforcement of certain laws, such as laws against

vagrancy, resulted in blacks continuing to be subjected to involuntary servitude in some cases, particularly in the South.

[14] See also

Black Codes.

Southern states hired out prisoners to private companies and interests as

convict lease labor to pay off court fees for such offenses. As these states made the lessees responsible for the prisoners' food, clothing and housing, these states did not build any prisons until late in the nineteenth century. Law enforcement and businessmen colluded to entrap freedmen and convict them, so they could gain revenues from convict lease labor.

Interpretation

Involuntary servitude

No offenses against the Thirteenth Amendment have been prosecuted since 1947.

[15][16]

Psychological coercion had been the primary means of forcing involuntary servitude in

United States v. Ingalls, 73 F. Supp. 76, 77 (S.D. Cal. 1947).

[17] However, in

United States v. Kozminski, 487

U.S. 931 (1988), the Supreme Court ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment did not prohibit compulsion of servitude through psychological coercion.

[18][19] Kozminski limited involuntary servitude to those situations when the master subjects the servant to:

- threatened or actual physical force,

- threatened or actual state-imposed legal coercion, or

- fraud or deceit where the servant is a minor, an immigrant or mentally incompetent.

The

Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, P.L. 106-386, updated the federal anti-slavery statutes to include victims who are enslaved through psychological coercion, even if there was no physical coercion.

[20][21]

Definitions of conditions addressed by Thirteenth Amendment

- Peonage[23]

- Refers to a person in "debt servitude," or involuntary servitude tied to the payment of a debt. Compulsion to servitude includes the use of force, the threat of force, or the threat of legal coercion to compel a person to work.

- Involuntary servitude[24]

- Refers to a person held by actual force, threats of force, or threats of legal coercion in a condition of slavery – compulsory service or labor against his or her will. This includes the condition in which people are compelled to work by a "climate of fear" evoked by the use of force, the threat of force, or the threat of legal coercion (i.e., suffer legal consequences unless compliant with demands made upon them) which is sufficient to compel service. In Bailey v. Alabama (1911), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that peonage laws violated the amendment's ban on involuntary servitude.

- Requiring specific performance as a remedy for breach of personal services contracts has been viewed as a form of involuntary servitude by some scholars and courts, though other jurisdictions and scholars have rejected this argument; it is a popular rule in academia and many local jurisdictions, but has never been upheld by higher courts.[25]

- Forced labor[26]

- Labor or service obtained by:

- threats of serious harm or physical restraint;

- any scheme, plan, or pattern intended to cause a person to believe he would suffer serious harm or physical restraint if he did not perform such labor or services:

- the abuse or threatened abuse of law or the legal process.

Enforcement (Section 2)

Threat of legal consequences

Victims of human trafficking and other conditions of forced labor are commonly coerced by threat of legal actions to their detriment. Victims of forced labor and trafficking are protected by Title 18 of the U.S. Code.

[27]

- Title 18, U.S.C., Section 241 – Conspiracy Against Rights:[28]

Conspiracy to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person's rights or privileges secured by the Constitution or the laws of the United States

- Title 18, U.S.C., Section 242 – Deprivation of Rights Under Color of Law:[29]

It is a crime for any person acting under color of law (federal, state or local officials who enforce statutes, ordinances, regulations, or customs) to willfully deprive or cause to be deprived the rights, privileges, or immunities of any person secured or protected by the Constitution and laws of the U.S. This includes willfully subjecting or causing to be subjected any person to different punishments, pains, or penalties, than those prescribed for punishment of citizens on account of such person being an alien or by reason of his/her color or race.

Proposal and ratification

Ratified amendment, 1865

Ratified amendment post-enactment, 1865–1870

Ratified amendment after first rejecting amendment, 1866–1995

The Thirteenth Amendment was proposed by the

Thirty-eighth United States Congress, on January 31, 1865. The amendment was adopted on December 6, 1865, when

Georgia ratified it. On December 18, 1865,

Secretary of State William H. Seward, proclaimed the amendment to have been ratified by the legislatures of 27 of the then 36 states. All 36 states as of 1865 eventually ratified the amendment. The ratification dates are:

[30]

- Illinois (February 1, 1865)

- Rhode Island (February 2, 1865)

- Michigan (February 3, 1865)

- Maryland (February 3, 1865)

- New York (February 3, 1865)

- Pennsylvania (February 3, 1865)

- West Virginia (February 3, 1865)

- Missouri (February 6, 1865)

- Maine (February 7, 1865)

- Kansas (February 7, 1865)

- Massachusetts (February 7, 1865)

- Virginia (February 9, 1865) - ratified by the Unionist Restored Government of Virginia

- Ohio (February 10, 1865)

- Indiana (February 13, 1865)

- Nevada (February 16, 1865)

- Louisiana (February 17, 1865)

- Minnesota (February 23, 1865)

- Wisconsin (February 24, 1865)

- Vermont (March 8, 1865)

- Tennessee (April 7, 1865)

- Arkansas (April 14, 1865)

- Connecticut (May 4, 1865)

- New Hampshire (July 1, 1865)

- South Carolina (November 13, 1865)

- Alabama (December 2, 1865)

- North Carolina (December 4, 1865)

- Georgia (December 6, 1865)

Ratification was completed on December 6, 1865. The amendment was subsequently ratified by the following states:

- Oregon (December 8, 1865)

- California (December 19, 1865)

- Florida (December 28, 1865, reaffirmed on June 9, 1869)

- Iowa (January 15, 1866)

- New Jersey (January 23, 1866, after having rejected it on March 16, 1865)

- Texas (February 18, 1870)

- Delaware (February 12, 1901, after having rejected it on February 8, 1865)

- Kentucky (March 18, 1976, after having rejected it on February 24, 1865)

- Mississippi (March 16, 1995, after having rejected it on December 5, 1865)

For unknown reasons, Mississippi's 1995 ratification was not formally filed with the

Archivist of the United States. The ratification was forwarded to the Office of the Federal Register on January 30, 2013, and on February 7, 2013, the director of the Register certified that he had received the ratification and that it was official.

[31]

Earlier proposed Thirteenth Amendments

Two amendments proposed by the Congress would have become the Thirteenth Amendment; neither was ratified by the states.

- Titles of Nobility Amendment, proposed by the Congress in 1810 and ratified by twelve states, would have revoked the citizenship of anyone either (1) accepting a foreign title of nobility or (2) accepting any foreign payment without Congressional authorization.

- The Corwin Amendment was passed by the House on February 28, 1861 and the Senate on March 2, 1861. It was ratified by two states: Ohio and Maryland.[32] This proposed amendment would have forbidden the adopting of any constitutional amendment abolishing or restricting slavery, or permitting the Congress to do so. This proposal was an unsuccessful attempt to persuade the border states not to secede from the Union.

Abraham Lincoln, in his first inaugural address on March 4, 1861, specifically referenced the Corwin Amendment:

[33][34]

"I understand a proposed amendment to the Constitution . . . has passed Congress, to the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service. I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable."

See also

Notes